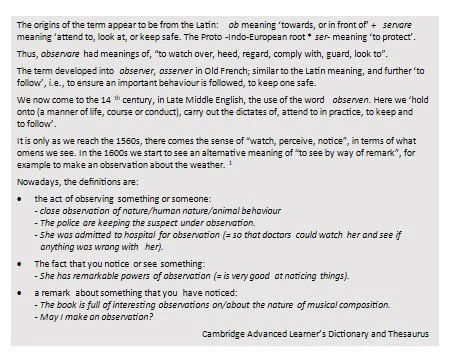

Observation n. and reasons for it in teaching

Armed with the knowledge of the word’s early roots, I would like to make a few observations about its use in the teaching profession.

In teaching, in my experience of the last twenty-something years, the term ‘observation’ would spark fear in most of us and bullishness in those very confident few. With it came ‘evaluation’ and feelings of vulnerability, exposure, powerlessness, fear, inadequacy amongst others. If the term ‘inspection’ came with it, generally followed a more solid sense of panic, hysteria, and sickness. This was the history of the use of observation of lessons as a tool to decide if you were doing a good enough job etc.

Now I’m not saying that evaluating teachers is the wrong thing to do. From a political viewpoint, in the public sector, the British people through their taxes pay the salary. They do this with expectation that teachers and schools will provide a high-quality education, with that money, for their children, for the nation’s children. And of course, there are all sorts of good reasons to do so. Of course, over time, what constitutes a high-quality education has changed; sometimes rather quickly, leaving behind some perfectly competent teachers to flounder because they are not demonstrating the indicators for that quality, the indicators which have also changed over time. Some have even been debunked. And it should not matter if a school is in an area of wealth and prosperity or situated in a ward with deep child-poverty, the quality should result in the same opportunities for those children. In fact, it shouldn’t matter which teacher is in the classroom teaching the child.

The data tells us this not to be the case. Students from some schools leave with a high probability of success in the world, of being healthy and as happy as anyone else, some do not. Students in some classes make more progress and do better in exams than others. And some teachers seem to be the teachers of those classes and those students.

The theory goes that the most effective teachers produce the effect that the students in their classes learn better by many months than less effective ones.

Now if we ignore the complex interactions between student and teachers over time, and the nature of the way learning is not a steady line of progress, and if we trust that the growing body of research is giving us information of a high quality, then we can begin to identify behaviours, processes and cultures in classrooms that can elevate the learning opportunities for all children. People who are wiser, more knowledgeable, and more experienced in many fields than I am believe this to be true and are sharing a ‘playbook’ for teachers and schools to use. Hence, I shall also use it and all its parts, until better evidence comes to the fore. I will also endeavour become ever better read. This is a tall order when one is teaching in schools, so we end up having to trust someone; some teachers decide that that someone is themselves, based on their own knowledge and experience, in the context of where they work. It is a view that has some validity, without necessarily the reliability of peer review and detailed analysis.

Returning to our evaluation argument then. If a leader, who is responsible for the children in their school allows less high-quality teaching, I would argue this is ethically wrong. Like in the health sector, one should do no harm, and I would suggest that knowingly allowing students to experience less than is possible, is doing harm to them, especially when compared to children leaving schools where this is not the case. So, it is important to evaluate the quality of a teacher’s performance and its effect on students; yet one lesson, or worse one 20 minutes observation cannot tell us about the quality of teaching and learning of a specific teacher.

A teacher can typically be in a classroom for 1,350 minutes in a week and depending on the subject they teach can be interacting with hundreds of individuals in that week. They are drawing on a huge schema of knowledge of their subject and specifically this curriculum and how it will be assessed; using deep knowledge of pathways through that curriculum, which best suit the most children and the other ways too so they can apply these when the moment to do so pops up. They are constantly reading the room, reading the responses, making sense of what they notice and making decisions in the moment to smoothly carry these young people through a type of narrative, through a concept, building on what students already know and attempting to undermine what they know which is wrong. And then there is the behaviour- the trust and mutual respect to bring about an agreed culture of high expectations with no wasted learning time; just as you think you’ve reached the flag, someone is having a bad day, some six could be having a better time not putting in the effort because ‘what’s the point’, and so you riffle through all your past experiences and managing your own emotions, despite the fact you haven’t had time for the toilet and missed breakfast, you find a few solutions that might work to get everyone back on track.

No. One observation of a teacher is not enough to tell you about the quality of the teaching and learning that happens in their room. Instead, leaders must look through many lenses to mine for data; this will point them towards some conclusions, especially over time.

Observations can work towards an evaluation of the quality of education in a school, because a large sample of lessons, teachers, students, and subject areas can be observed in a short period of time. It is the sample size that informs the analysis.

Nowadays thankfully, Ofsted and hence UK schools have shifted away from observation as evaluation and towards using observation as a tool for feedback, through a coaching model of professional learning. Again, this cannot inform us of the quality of teaching, on its own, nor even perhaps over time. It can enable a professional to be informed of specific behaviours and processes, and their effects. This knowledge when coupled with insights from expert research, can point teachers towards more effective choices. If partnered with a critical friend, a coach, these reflections, and efforts to change their actions in class, can transform a teacher’s practice. And the evidence suggests that higher quality teaching results in students who learn better and have more fulfilling experiences.

Nevertheless, in many cases observation still garners some restlessness and nervousness: performance anxiety. Quite naturally.

The origins of the word observation are to follow, to have regard to attend to in practice. These all have connotations for those of us who practice in schools. There are rules about professional behaviours, there is multiple guidance of how we should follow; this to protect and keep safe the students, their learning, and their future opportunities. We in our reflections every day, can attend to what we are doing and question it and if there are better ways of achieving our goals; we can notice by carefully observing the details. By unpacking what the expert research (and our own expertise, including knowledge and regard to the students in our care) tells us is effective, in its granulated form, means we can consciously build our repertoire and toolkit, so that in the complex and busy world of the everyday classroom, we know what to do for the best. Every minute, every child.

On an observation deck, one sees far and can get the big picture and mood. The big picture is hard to describe, without describing the granular details we see. The observer can collect those details and as partners we craft a teacher’s practice into one of more depth, clarity, and flow. It is probably only then we can make an observation on the quality of the teaching and learning. Then we watch over, guard and attend to with care, our precious service to the generations of young people we work for.

References

1 https://www.etymonline.com/word/observe